“It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best, since you have to sweat up the hills and coast down them. Thus you remember them as they actually are, while in a motor car only a high hill impresses you, and you have no such accurate remembrance of country you have driven through as you gain by riding a bicycle.” ~Ernest Hemingway

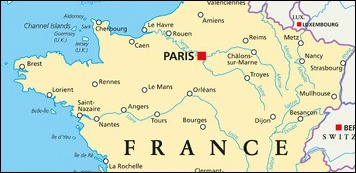

Paris-Brest-Paris. 1200 kilometers across France with 5000+ audacious cyclists from around the globe. The biggest Randonneruing event in the world occurs every four years, and the next Grande Randonnee will be held in August of 2015.

While most people in the US are familiar with the Tour de France, and many riders know about races like RAAM (Race Across America) and 508, outside of the randonneuring community, their friends and family, and the entire country of France, nobody’s ever heard of PBP (Paris-Brest-Paris).

Racers are in the forefront of the public image of cycling with everyone rooting for the guy who is the strongest and fastest. There’s sponsorship, media coverage, public awareness, prize money. While racers bask in the ignominious glory of public scrutiny, randonneurs silently ride, often solo, putting in at least as many miles without the support of a peloton to shelter them from headwinds, a team to advance them over the hardest climbs, and a convoy of follow-vehicles carrying spare bike parts and gallons of liquid nutrition. While top racers are darlings of the public, the only accolade for the randonneur is the knowledge that he or she has managed, despite weather, mechanicals, sleep deprivation, and encounters with local wildlife, to finish what was started. Or not.

Racers are in the forefront of the public image of cycling with everyone rooting for the guy who is the strongest and fastest. There’s sponsorship, media coverage, public awareness, prize money. While racers bask in the ignominious glory of public scrutiny, randonneurs silently ride, often solo, putting in at least as many miles without the support of a peloton to shelter them from headwinds, a team to advance them over the hardest climbs, and a convoy of follow-vehicles carrying spare bike parts and gallons of liquid nutrition. While top racers are darlings of the public, the only accolade for the randonneur is the knowledge that he or she has managed, despite weather, mechanicals, sleep deprivation, and encounters with local wildlife, to finish what was started. Or not.

Randonneuring is a sport where individual riders are challenged to ride extreme distances while supporting themselves. There are brevets where a local club organizes a group ride according to the rules of ACP (Audax Club Parisien, the parent world-wide organization for the sport). There are permanents: rides which are mapped out, approved by RUSA, and “owned” by a local club member, which can be ridden by any rider at any time as long as permission is obtained, a waiver signed, and passage proven. There are Grand Randonnees which are the longest of brevets with distances of 1000km, 1200km, and even 1500km. For perspective, 508 miles is approximately 800 kilometers.

Randonneurs of the USA (RUSA) was established in 1998 and exists to support local randonneuring clubs and help them interface with ACP. Members are encouraged to work towards a variety of awards: the R-12 where a rider completes a permanent or brevet of at least 200 kilometers every calendar month for 12 consecutive months; the Ultra R-12 where a rider has completed ten R-12 awards; the Super Randonneur which requires riding ACP brevets of 200km, 300km, 400km, and 600km in a calendar year. There are awards for achieving 5000km of ACP events over four years, and the K-Hound for those intrepid souls who manage to ride 10,000km of ACP events in a calendar year. The list goes on. Nobody has ever heard of any of this, unless he or she has stumbled upon RUSA and joined the club. But RUSA is growing. In 2014, membership topped the 10,000 mark.

PBP is the oldest bicycling event still being held on a regular basis. It got its start in 1891 as a race to test the mechanical reliability of the bicycle and the physical tenacity of the rider, and was open only to male French cyclists who were each allowed ten paid pacers to help with drafting and repair of mechanical issues. Over 400 riders entered the inaugural event, and about 200 actually started. The first rider to finish was Charles Terront who pedaled into Paris in slightly less than 72 hours. 100 ragged survivors gradually trickled into Paris over the following seven days, and another 100 limped their bicycles to a train station to get themselves home.

PBP is the oldest bicycling event still being held on a regular basis. It got its start in 1891 as a race to test the mechanical reliability of the bicycle and the physical tenacity of the rider, and was open only to male French cyclists who were each allowed ten paid pacers to help with drafting and repair of mechanical issues. Over 400 riders entered the inaugural event, and about 200 actually started. The first rider to finish was Charles Terront who pedaled into Paris in slightly less than 72 hours. 100 ragged survivors gradually trickled into Paris over the following seven days, and another 100 limped their bicycles to a train station to get themselves home.

The event was initially held every 10 years, and the second time foreign cyclists were allowed to enter. While PBP was a professional race at its inception, in 1901 an amateur division was created allowing those who wanted to test their ability to tackle such a grueling event to attempt the ride. These amateur riders were the first randonneurs. The amateur division was dropped in 1931, and Audax Club Parisien stepped in and created a brevet to run alongside the race. 1931 also stands out in PBP history as this was the year Madame Germaine Danis became the first woman to successfully complete the course, clocking in at 88 hours on a tandem with her husband. The first solo woman also finished the course that year, with Madmoiselle Paulette Vassard completing the event in 93 hours.

There was no PBP held in 1941 due to the curfews imposed by Germans occupying France, but a post-war race was held in 1948 and the tradition of holding PBP in a year ending in “1” was resumed in 1951 which turned out to be the last time the event was held as a race. By 1956, criterium races had become popular. These events allowed racers to sleep at night, were less grueling, and paid better. Attempts at organizing PBP in 1956 and again in 1961 were cancelled due to lack of interest among racers. But interest among amateur cyclists continued to grow. 10 year intervals shrank to 5 year intervals, and the event has been held every 4 years since 1971 attracting riders from around the globe.

A substantial part of randonneuring events is self-sufficiency on the road. Support is minimal at best, and riders are expected to be able to manage their own nutrition and fix mechanicals in the field. There are time windows imposed for reaching various control points along the way and for finishing events. Unlike racing, if you arrive too early you have to wait until the control opens. If you arrive too late, you are disqualified. The time limits are the same regardless of the age or gender of the rider, the amount of climbing on the route, mechanical issues, and weather conditions.

A randonneur’s bike weighs at least a ton when fully loaded for a big ride because she will need to carry enough layers to comfortably survive 90+ degree daytime temperatures followed by 40 degree nights, and enough calories to make it for 100 miles or more. He needs to be prepared to eat off the bike if a control point has no open food establishments or if convenience store foraging leaves him with nothing his body will accept as food. She needs to be ready to deal with all the minor medical issues which happen on a long ride – headaches, muscle cramps, nausea, hypoglycemic jitters, saddle sores, and more. Most randonneurs will have a full complement of tools in their bike bags, because they need to be able to change tires, repair a broken chain, tweak a jammed derailleuer, and any number of other mechanical fixes. If the bike breaks down 200 miles from anything where his cell phone doesn’t work, the randonneur has to be able to deal with it. Keeping lights, navigation equipment, and a cell phone powered for multiple days is a challenge riders with a follow vehicle never have to face. Without a crew, everything about finishing is up to the individual. Self-sufficiency is empowering in ways you can’t imagine until you’ve been there.

A sea of randonneurs adorned in required reflective gear. Thanks to Michele Brougher for the photo 🙂

For brevets, clubs may provide support which ranges from a human being at a control point to sign brevet cards – a mechanism for proving the rider has made it to each control point within the appropriate time window – to offering group sleeping accommodations and hot meals for riders. Some Grand Randonnees offer overnight controls with mats to nap on and shower facilities. Some will allow riders a “drop bag” which will be brought by volunteers to a specified control, allowing them to stash items like a change of shorts or extra clothing. Others require that riders figure out where they are likely to need a break and book their own hotel rooms. Slower riders may choose to hedge their bets, carrying everything they may need and taking coffee naps on park benches wrapped in space blankets rather than getting a few hours of sleep at a control. Control points may include a manned control or may require the rider to make a purchase and submit a receipt from a local business. If a control is in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night when no businesses are likely to be open, there may be a requirement of dropping a postcard in a local mailbox or answering a trivia question (what color is the door on the local coffee shop?) on the brevet card. Individual riders are allowed to have people provide extra support, but only at specified control points. Most choose to minimize outside support, preferring the exercise of self-reliance.

Racers and randonneurs have a lot in common. Both like to spend many hours in the saddle, are willing to suffer mightily, ride in all weather, and enjoy the comraderie of encountering other riders on the road. Both try to constantly push themselves to find the boundaries of what is possible whether the focus is on being faster than other riders, beating a personal best, or seeing how much farther than the last “longest ride ever” they can go. But there are some key differences I’ve observed between the two groups.

Racers tend to be more competitive with other riders, while randonneurs tend to be more competitive with themselves. Racers tend to prefer riding with others, while randonneurs are content to spend countless hours alone with their thoughts. Racers are data-driven. They will spend hours analyzing the information from their power meters, looking at their wattage output and trying to fine-tune ways to maximize the output for longer and longer periods of time. They are content to ride the same route each week, looking for the incremental improvements which demonstrate their training program of high intensity intervals is working. Many hire coaches to help guide this process and help them break through the barriers to improved speed and strength. The objective is winning the race.

Randonneurs find this type of riding to be torturous. They just want to get out and ride. All day. And all night. And the next day. While I’ve seen a few randos on the road with power meters, I’ve seen more with an old-school wired cat-eye and a route sheet. Racers tend to have expensive equipment with bikes and helmets designed for maximum aerodynamics, super light-weight wheels, carbon shoes. Anywhere a fraction of an ounce can be shaved off it is, because it can make the difference between winning and second place in a close competition. Randonneurs tend to have older bikes with fenders, ride 28mm tires inflated to 60psi, use mountain biking shoes in case there is a compelling reason to “hike-a-bike”, and make liberal use of duct tape and bungee cords for securing various items to their steeds. Finishing the ride while making all of the control windows is important, not finishing first. While some randonneurs enter races with intent to win, most of the randonneurs I know who race are in it to challenge themselves and see if they can finish within the time limits. A race like the 508 may be a stepping stone between a 600k and a 1200k. If they finish other than dead last, it’s a bonus but not the objective.

A friend who rides five or more double centuries each year recently completed several days of a cycling camp attended mostly by racers and observed that while he found the prospect of holding on to a pack of riders who were considerably faster than him to be a daunting proposition, he had no concern about riding 100+ miles each day with climbing approaching 10000 feet. The racers he talked to had no problem with the speed training, but were concerned about having the ability to sustain the distance and the climbing for consecutive days. Racers train for speed and quick bursts of power, while the randonneur trains to be the Energizer Bunny, seeking the balance between speed and steadiness which allows him or her to keep going and going and going.

Please know that those last paragraphs are my personal observations and are in no way meant to disparage either group of riders. What qualifies me to make these observations? I’ve done plenty of randonneuring (three consecutive R-12 awards, two Super Randonneur awards, and an epic DNF on a 1200k attempt), dabbled in racing as a last minute addition to teams for the 2013 508 and 2014 Race Across the West, and have close friends in both camps. I exist in a world where a double century is just a training ride, and the words “Palomar Mountain” and “repeats” do fit into the same sentence.

I love the self-reliance, intensity, and solitude of randonneruing, but I also love racing. Having a follow-vehicle blasting music of my choosing through front-mounted speakers to keep me awake and motivated in the middle of the night is super different from chewing gum and singing show tunes to keep from nodding off while pedaling. Having crew who hand me fresh bottles of water and cater to my dietary whims is a fabulous luxury compared to picking from the dregs of some rural service station in the wee hours of the morning. The excitement of catching other riders and passing them is addictive. Planning for all the logistics of an ultra-race requires as much or more attention to every detail as planning for the logistics of a grand randonnee. For the randonnee, I only have to worry about my own needs. As a racer, I need to plan for the happiness and health of my crew. Just as I depend on them during the race, the preparation I do allows them to have the tools to help me.

The beautiful thing is that although most riders tend to prefer one type of riding over the other, an avid distance cyclist doesn’t have to be defined as a racer or a randonneur. Both aspects of the sport allow for personal and physical development as an athlete and provide myriad opportunities for new challenges. If you’ve done your first century and have the bug to see what it’s like to take on bigger things, I encourage you to look up your local RUSA chapter or check out endurance racing in your area. Whichever you choose as a starting point, you will be richly rewarded with outstanding fitness, friends who think you’re nuts while admiring your athletic prowess, and incredible stories from the road!

I’ll help get you through Paris-Brest-Paris if you help get me through Race Across the West… Deal?

You are uniquely qualified to write this. A rare person can live in two worlds.

It’s a DEAL, Murgaster! Excited to be doing PBP with you 🙂

Best description of pbp, interesting to learn about the history and development .You have been heading to pbp before you even knew about it. Good luck. I know we will all be super amazed since you continue to amaze me.

Thanks, Judy!!! You continue to do inspirational things yourself. Love hearing about all of YOUR adventures, too 🙂